Noori brothers sit down with Instep and talk about the remarkable year they’ve been having, the ongoing Punjab tour and cultivating a serious listener base

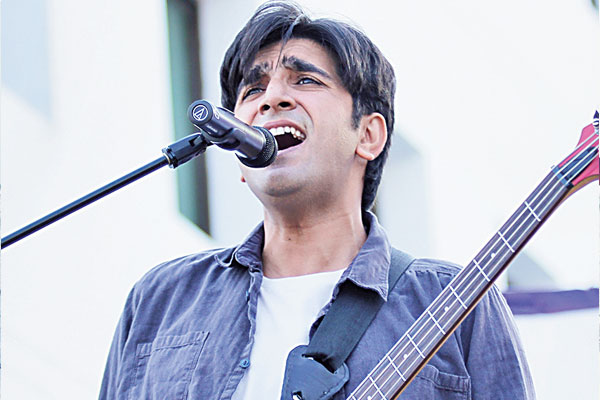

As I listen to the tape of my conversation with Noori brothers Ali Noor and Ali Hamza, who front and form one of Pakistan’s most cherished and still active music groups, what’s instantly palpable is that they refuse to conform to the norm and remain unpredictable.

While most artists who started out around the same time as Noori have either turned to acting in TV, films or both or have split up or split their focus to other facets of the entertainment business, for one reason or another, Noori remain a loveable anomaly who are still making their brand of music, presenting rock permutations that go beyond riffs and rage and weave a musical narrative that is both personal and national.

We meet on Sunday as Noori carve out precious time from their ongoing Punjab tour to come to Karachi for a whirlwind 24 hours where they not only met with the press but also gave fans in Karachi a chance to see them in action (alongside Sara Haider) at a popular mall.

Meeting at a PR agency’s office on a warm afternoon, I’m greeted by a mostly deserted office barring a few individuals.

The lethargy of Sunday, however, quickly vanishes upon meeting the band. Inside a room, lit brightly, brothers Noor and Hamza sit, dressed casually in jeans, t-shirts and Noor sporting a hoodie jacket, greets me warmly and with a hint of nostalgia as we reminisce my first interview with them, in Karachi, which happened almost a decade ago on the heels of the release of their second studio album, Peeli Patti Aur Raja Jaani Ki Gol Dunya.

When you meet Noori, you instantly feel invigorated not just by how passionate they are about what they do but also because they have this inherent ability to make people feel involved and connected. Whether it’s the fans or other artists or even a commissioned corporate/brand related project(s) – it is this quality that sets them apart from other entities.

I take out several sheets of paper, inundated with questions and they laugh heartily before quickly agreeing to answering as many question as I want. It’s a far cry from PR-coordinated interviews where ordinarily the questions often don’t veer away from one particular topic or occasions when artists remain reticent and inch away from saying anything about what matters most to them. Part of it is weariness induced by the cycle of persistently talking to the media but Noori thankfully show no signs of jaded cynicism.

Long story short, we want to cultivate a brand new listener base and take out lots of new songs,” says Noor. “When I say cultivate I mean listeners who take out time to listen to a song/record and not while you’re using Facebook and playing it on the side.

As we open our conversation from their most recent effort, a song that serves as the soundtrack to a beauty supermodel contest, Noor and Hamza admit that they agreed to do the project mostly because the idea behind it is to appreciate beauty in the mundane, and inculcate the simple but powerful belief that ordinary people are beautiful; it also speaks of internal transformation. In this day and age of photo-shopped images, Noori’s approach to the project is certainly important.

Having collaborated with Sara Haider on the said song, our conversation invariably moves to women in music and Noori, who have worked with several artists this year including not just Sara Haider but also Momina Mustehsan, Quratulain Balouch and many more, maintain that the current crop of women working in music are exceptionally hardworking.

“Sara Haider is very driven and she wants to learn a lot and she’s very serious-minded. Not just her but Rachel (Viccaji) and Zoe Viccaji,” says Ali Noor, a rock god who can be outrageous one minute, laughing infectiously, and sober the next with ease.

Hamza, the poet and the more restrained of the two echoing Noor sums it up best: “The artists of this generation, the ones coming into the music scene… a) they are very-talented, b) they have a good head on their shoulders, that’s the really good part.”

“None of them are in a hurry and they have a vision,” adds Noor. “The reason why I’m talking about this is because I had a chance to speak to them and work with them during Coke Studio.”

The year 2016 has been a significant one for Noori. Picking up the LSA Best Album trophy for their third studio album, Begum Gul Bakaoli Sarfarosh, which released last year to critical and commercial acclaim after a gap of a decade, they’ve been working with the kind of regularity that is rare for a mainstream name. A remarkable stint on Coke Studio as music directors, three original songs accompanied with music videos via Cornetto Pop Rock plus a gorgeous Indo-Pak single collaboration and the revival and reinvention of BIY Music, the brothers are in a space where they are not only enjoying creating music and playing it out for fans any and every chance they get but one which allows them to shape a vision and their place in the sometimes fickle world of music. And as always, their loyalty lies with the fans; the ones who stand in line to get a CD signed or like the gaggle of giggling girls who were hoping I’d introduce them to the band as I was walking one step behind Noor and Hamza at a Mall when we met in Karachi last summer to talk about their new record, which the brothers released in a classic DIY effort that they’ve become known for.

Surprisingly enough, despite doing commissioned projects, they are not big fans of it. “The problem with commissioned work is that you are always trying to satisfy the client,” explains Noor. “We’ve managed to find an interesting middle ground where we take all these clients and become very close with them on a creative level. We become good friends because if we don’t get along with the people, it doesn’t work. So the real story here is that we get them involved in the process. There is never a revision in what we do. It becomes actually very memorable as opposed to being a bearable experience.”

I tell them what I’ve said in other Noori stories before: it’s been a monumental year for the band and the amount of original work they’ve done including their smart tackling of Coke Studio as music directors, is worth infinite applause.

“We sat on our ass for ten years,” says Noor as Hamza corrects him, “We were playing live music…”

I press on about the collaboration with Ali Azmat, a song called ‘Dildara’ that is both endearing and iconic.

“Ali Azmat changed Ali Noor,” laughs Hamza.

Noor admits that the process of working with several artists through one project or another has led to a personal, internal transformation. “Not a perfectionist at all but within me, a confused, unsure man has decided to just say f*** it. Jo ayega dekha jaiye ga… After that, my whole funda changed, to be a doer. I think that is what’s happened.”

“I think the real thing that’s happening in all this is the changes that are coming from within us,” confesses Hamza.

“There’s a strange karmic thing going on,” says Noor introspectively on the monumental year they’ve been having.

As the conversation shifts again and I ask the brothers about their ongoing Punjab tour that is organized by Punjab Group of Colleges and is taking them to Okara, Bahawalpur, Multan, Faisalabad, Sargodha, Gujranwala, Gujrat, Sialkot, Islamabad and Lahore, the emotion in the room changes.

“You know how you have tours abroad, it’s like that,” says Noor. “The shows start on time, the audience is in place and the girls make the ultimate audience. The irony is that this audience goes neglected.

This audience is so responsive. We realized that the theme of Noori is so applicable to them. I kind of wish that we had planned some workshops; we can’t mess with the schedule but as we were singing ‘Suno Ke Main Hoon Jawan’, we realized that we may have gone ahead but this audience never got a chance to hear these songs.”

The shows that we as an urban audience can take for granted in bigger cities like Karachi and Lahore are a revelation to people in other cities. And Noori know it too. To them, the tour has led to the opening up of another world, a whole new horizon full of dedicated fans and this audience will, in all probability, earn more chances to see the band in the future.

I ask them if working on Coke Studio with so many artists from the music scene has changed their perception of the industry. What’s disarmingly charming is how quickly Noor makes it a point to say that as far as Noori were concerned, Bilal Maqsood was the third music director. “He was really involved in the process with us. And he was like the third director. Other people maybe opted for autonomy but for us without Bilal, we simply wouldn’t start. He would sit with us.”

Answering the questions with his usual honesty, Noor says, “Working with other people gave us a chance to learn about their different aspirations. It was also a reality-check that this is what it is.”

Answering the questions with his usual honesty, Noor says, “Working with other people gave us a chance to learn about their different aspirations. It was also a reality-check that this is what it is.”

Moving towards the indie music scene, which unlike the mainstream side of music, is filled with artists who insist on doing quality original work and sadly go uncounted when one speaks of the music scene, Noori admit that they must be counted. “For that to happen, they have to cross the threshold. Everyone has a starting point but they’re unable to find it. I really want to do indie, and I will do it. Indie artists are very talented.”

“No matter whom I listen to, they have something,” says Hamza.

“We did what we did because I thought every other band was shit,” says Noor. “I was uninspired by everybody and I’m sure they feel the same way. I don’t think Noori inspire them that way. They want to do their own thing, sing in English, do electronica but I guess the only thing I was able to figure out and what they need to figure out is how to cross that threshold.”

Aside from doing their own music, Noori have also revived BIY Records, now known as BIY Music, through which they released their own album BGBS last year and through which others hope to follow suit such as one Haroon Shahid of SYMT-fame.

“We’re figuring it out,” says Noor. “The only thing we’ve realized now is that we need content creation mechanism,” says Noor. “The amount of time in which we actually get things done. But most of all, our interest is, to be honest, not to pander to people’s existing sensibilities. It goes against the grain of what we want to do. But we were doing it. We want to cultivate a serious listener. For example, you are a keen, serious listener. That number has dwindled to such an extent that it’s stupid. You’re doing covers because they are familiar, you are re-working old songs and they’re familiar too. What does that signify? That people are becoming dumb.”

“Everything is being dumbed down,” says Hamza.

“Long story short, we want to cultivate a brand new listener base and take out lots of new songs,” says Noor. “When I say cultivate I mean listeners who take out time to listen to a song/record and not while you’re using Facebook and playing it on the side. That’s f***ed up, yaar.”

To Noori, numbers don’t mean too much. They neither have millions of fans on Facebook nor do they care too much about digital statistics.

“You’ll die as an artist if you look at numbers, trust me,” says Hamza.

And unlike a lot of other artists in the spotlight, Noori are not trolled online or receive abusive messages.

“Once in a blue moon,” admits Hamza.

Noori fans are only angered when they think the band is doing commercial things. “We get hate-mail on doing commercial stuff but I think that number is small.” Noor says.

As we come to the end of the interview and only because of my realization that others are waiting in line to interview the band, Noori brothers confess that aside from the band’s revitalized return, they aim to diversify, create different spaces filled with different styles of expressions, pursue solo projects while keeping the promise of Noori alive.

“Noori is now going to fly in terms of creative ideas,” says Noor on a parting note. And given their recent track record, we, as longtime fans, can only say encore.

Published in The News, November 20th, 2016.

Answering the questions with his usual honesty, Noor says, “Working with other people gave us a chance to learn about their different aspirations. It was also a reality-check that this is what it is.”

Answering the questions with his usual honesty, Noor says, “Working with other people gave us a chance to learn about their different aspirations. It was also a reality-check that this is what it is.”